The test would cost around a dollar, and it would provide results in about the time it takes to brew and down the day’s first cup of coffee. A negative result would mean it was safe to go to work or to school, as long as other basic mitigation measures—mask wearing, social distancing, and handwashing—were practiced. A positive result, seconded by a different test, would necessitate self-isolation.

Given that an estimated 40% of people with SARS-CoV-2 infection have no symptoms but can still transmit the virus to others, widespread, do-it-yourself (DIY) rapid testing for presymptomatic or asymptomatic people could end the exponential spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), said Mina. An epidemiologist, pathologist, and member of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, he also directs a recently launched volunteer organization called Rapid Tests.

By contrast, the gold standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test used to diagnose COVID-19 requires laboratory processing that sometimes takes days, not minutes, to obtain results, due to backlogs and supply shortages. So an individual could be negative when tested but positive by the time the result is returned. As Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, said in an interview, “a PCR test that [gives] results back in 8 days is a worthless test.”

Frequent rapid testing “could potentially be game-changing before the vaccines,” said Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, an infectious disease physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and an advisor to Rapid Tests. “The opening up of society could happen much sooner.”

Two dozen companies are interested in developing rapid SARS-CoV-2 at-home tests, like those for HIV or pregnancy, said Mara Aspinall, MBA, cofounder of the Biomedical Diagnostics program at Arizona State University. “We’re taking a modern centralized laboratory and shrinking it onto a plastic-covered strip,” said Bobby Brooke Herrera, PhD, the cofounder and chief executive officer (CEO) of one of those companies, E25Bio in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Although roughly a handful of rapid SARS-CoV-2 tests are being used in the US, at present, a dirt-cheap DIY rapid test exists only in the imaginations of those who think it’s vital for safely reopening the US and on the drawing boards of biotech companies working toward that goal. Whether it’s possible to bring the cost down to $1 remains to be seen, as does who would pay for it and how it would be distributed, among other questions.

Failure of the Test or the Tested?

Rapid SARS-CoV-2 tests have received some bad press recently, fallout from a superspreader event: the September 26 Rose Garden announcement of President Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Amy Coney Barrett, to replace the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“Use of Coronavirus Rapid Tests May Have Fueled White House Covid-19 Cluster, Experts Say,” the Wall Street Journal stated in a headline.

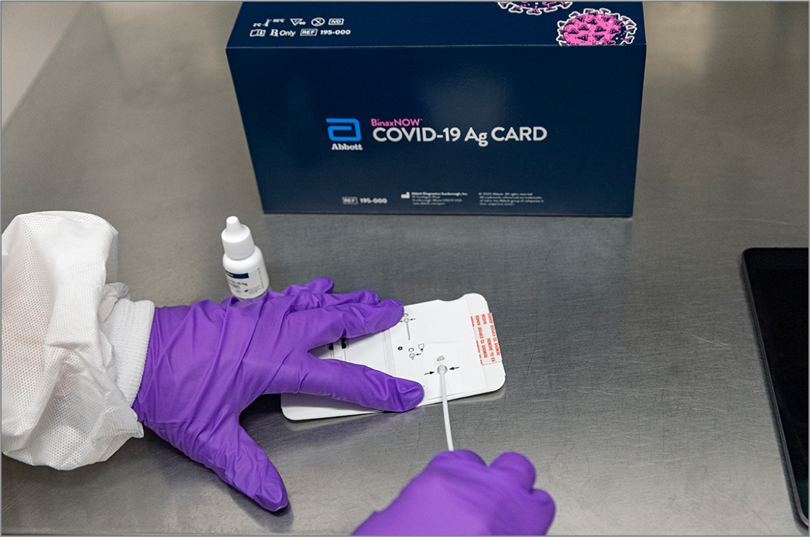

At least 12 people who attended the Rose Garden event, including President Trump and First Lady Melania Trump, were subsequently diagnosed with COVID-19, even though the White House reportedly has been using Abbott’s BinaxNOW rapid COVID-19 antigen test to screen visitors and staff members coming in close contact with the president. In an October 12 memo, White House physician Sean Conley, DO, said that after recovering from COVID-19, President Trump had twice tested negative using the BinaxNOW test.

The test received an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on August 26. (In an October 2 statement, Abbott said it did not know who was tested or which test was used at the Rose Garden event; John Koval, Abbott’s director of public affairs for rapid diagnostics, declined to provide anyone to comment for this story.)

BinaxNOW is one of 6 point-of-care rapid antigen tests that had received an EUA from the FDA as of October 10. The first, in May, was Quidel Corporation’s Sofia 2; on October 2, the FDA also granted an EUA for Quidel’s antigen test that checks for influenza as well as SARS-CoV-2 antigens. The other 3 are the BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company) Veritor System, the LumiraDX test, made by a UK company, and AccessBio’s CareStart. Only BinaxNOW does not require a special instrument on which to run the tests; a credit card–sized testing card similar in design to some pregnancy tests provides results, according to the FDA.

While PCR tests detect genetic material from SARS-CoV-2, antigen tests pick up molecules on the surface of the virus. “Antigen tests are very specific for the virus, but are not as sensitive as molecular PCR tests,” the FDA noted in the press release announcing Quidel’s Sofia 2 test. “This means that positive results from antigen tests are highly accurate, but there is a higher chance of false negatives….” Symptomatic people with a negative antigen test may need to have their results confirmed with a PCR test, according to the FDA.

None of the 6 tests, all of which require a nasal or nasopharyngeal swab, is DIY or as cheap as $1 apiece; Abbott’s is $5, while Quidel’s is $23, plus the cost of the health care professional who orders them. Even so, they’re cheaper than a PCR test, which starts at about $75. The FDA has authorized the antigen tests only for symptomatic individuals, although Admiral Brett Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health in the Trump administration, recently tweeted that the tests could be used off-label for asymptomatic people. (The latest Cochrane Review of the evidence for rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection noted that none of the relevant studies—a quarter of which had not been peer reviewed—published as of May 25 reported including any samples from asymptomatic people.)

“We think antigen tests have the greatest potential for screening asymptomatic people,” said Aspinall, a contributor to The Rockefeller Foundation’s COVID-19 National Testing & Tracing Action Plan, which calls for administering at least 25 million rapid antigen tests, on top of 5 million PCR tests, per week in the US this fall.

Not Doing the Right Thing

Rapid tests alone can’t halt the spread of SARS-CoV-2, Mina noted at a press conference October 2, hours after Trump tweeted that he tested positive. No test is perfect, and, depending on the technology used, people could still test negative early in the course of their infection.

“I think a lot of people…think that rapid tests aren’t working in the White House, but that’s completely false,” Mina said at the press conference. “One of the things that’s important here is that testing will never stop somebody from getting the virus.”

Even Giroir made that point, in a press release issued 2 days after the Rose Garden event. “Testing does not substitute for avoiding crowded indoor spaces, washing hands, or wearing a mask when you can’t physically distance,” he said. “Further, a negative test today does not mean that you won’t be positive tomorrow. Combining personal responsibility with smart testing is a key component of the administration’s national strategy for combatting COVID-19….”

However, as photos and videos of the Rose Garden event have shown, neither President Trump nor the other guests who became infected were wearing masks or practicing social distancing. “So how exactly he got [COVID-19] is completely separate from whether or not the testing program is succeeding,” Mina said at the press conference.

Pathologist Geoffrey Baird, MD, PhD, on the other hand, would say the White House outbreak makes the point that frequent SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests won’t hasten the pandemic’s end.

“The transmission of the virus is caused by human behavior. It’s not caused by lack of testing,” said Baird, chair of laboratory medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and coauthor of a recent op-ed piece questioning the utility of rapid SARS-CoV-2 tests. “Human behavior trumps technology every single time,” he said in an interview.

Skeptics such as Baird wonder how people who won’t even wear a mask could be counted on to test frequently and, if positive, self-isolate, especially if they’re asymptomatic.

Michael Osterholm, PhD, founder and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, questions whether people would faithfully test themselves. After all, many patients don’t take their medication as prescribed.

“Can you actually change the course of the pandemic with this type of testing?” Osterholm, who contributed to The Rockefeller Foundation’s COVID-19 action plan, said in an interview. “The challenge I have is just linking the behavior and the willingness to do this. If I’m a well person, do I get up every day and take this test, like I take my vitamins?”

Mina acknowledged that such concerns are warranted. “We just have to get on every TV and radio station and buy ads on Google to drill home the message that these don’t mean you have no ability to transmit if you’re negative,” he said in an interview. “If you’re positive, then definitely stay home.”

If huge numbers of people ignored their results or tossed their test strips in the trash, screening would still be useful, Mina argues. “There are going to be people who want to use it,” he said. “Once their kid is back in school, people are going to want to know if their kid is positive.”

Even if only 20% of individuals use rapid antigen tests frequently, that’s 20% more asymptomatic people who could learn whether they’re infected and need to isolate, Adalja said, calling rapid tests a harm reduction strategy.

Questions About Accuracy

Rapid antigen tests aren’t as sensitive as PCR tests, but they don’t have to be, proponents say.

Antigen tests don’t have the same role as PCR tests, which are needed when “the head of the microbiology lab wants to make sure that the patient in the emergency department does not have the disease,” Walensky said. “In patient settings, they can’t be wrong. Having a false negative means [infected] people are not isolated.”

However, perfection is an unnecessarily high standard for rapidly screening asymptomatic people, a task for which “we have nothing right now,” Adalja noted.

Mina, Walensky, Herrera, and other proponents of antigen-based tests argue that they are at least as good as PCR in the early phase of infection, when viral load and infectivity are highest. False negatives would most likely be those at the tail end of their infection, with low viral loads, so they couldn’t transmit it anyway. Those are the people PCR is especially good at identifying, the thinking goes.

That might be true, “but there’s no data,” Matthew Pettengill, PhD, scientific director of clinical microbiology at Thomas Jefferson University, said in an interview. “They need some data that show the correlation [of antigen test results] with infectivity is actually strong.” Pettengill recently coauthored an editorial questioning whether the US could test its way out of the pandemic.

Baird said he doubts there ever will be data to prove that, in part because the tests don’t show whether someone just missed the threshold for a positive or negative result.

“I prefer to have a 90% sensitive test to a 70% sensitive test if all things are equal. But all things aren’t equal,” said Walensky, whose recent findings in JAMA Network Open showed that screening every 2 days with a rapid, inexpensive SARS-CoV-2 test, even one with a sensitivity as low as about 70%, would allow for safely reopening colleges. “We have to understand what its upsides and its downsides are,” she said of rapid antigen tests.

Nevada’s recent experience with rapid testing in nursing homes might have revealed a downside. In early October, the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services directed nursing homes to stop using all rapid antigen tests because of a high rate of false positives with the Quidel and BD tests.

Of 3725 tests performed at a dozen facilities, 60 were positive. Samples from 39 of the positive tests were sent for confirmatory PCR tests, and of those, 23 tested negative. Half of the 30 BD positive tests were negative with PCR; 8 of 9 Quidel positive tests were negative with PCR.

“The concern is moving a false-positive vulnerable individual into a unit with known positive COVID-19 patients,” according to the health department, which noted that the antigen tests might not be to blame for the conflicting results. Other possible explanations, the department said, were improperly performed tests, delays in conducting the confirmatory PCR test, and low prevalence and incidence of COVID-19.

A week later, though, the Nevada health department rescinded the order after Giroir sent a letter calling it “improper” under federal law and “based on a lack of knowledge or bias.” The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) subsequently recommended that Nevada nursing homes confirm all positive and negative rapid antigen test results with PCR testing.

Game On

At least one popular activity, college sports, is (almost) back to normal at some schools due to rapid antigen tests.

In part because of Quidel’s Sofia 2 test, the Pac-12 and Big Ten conferences reversed earlier decisions to cancel the 2020-2021 football season. “It allows them to reengage with contact sports, both women’s and men’s, which is an important part of college life,” Quidel CEO Douglas Bryant said in an interview.

The Big 12 Conference and the Southeastern Conference (SEC), which had never announced plans to cancel football, also test athletes with the Sofia 2, Bryant said.

Quidel is working with the researchers at the Pac-12 schools to collect information about the use of the Sofia 2 test in asymptomatic individuals, he said.

“It’s our hope…that we can develop an algorithm that would help grandmas and grandpas get back together with their families, that would help schoolkids get back to their classrooms, and ultimately would get more Americans back to their workplace and feel comfortable,” Bryant said.

Quidel took a step closer toward that last goal in late September when the company began screening all employees weekly with the Sofia 2 test, Bryant said.

The San Diego–based company is also running a pilot testing program at a local private school with kindergarten through 12th grade (K-12), he said. Students who opt not to get tested won’t be allowed on campus and will have to take their classes online, Bryant said, adding that the school “spent a lot of time educating the parents” about testing’s role.

A report released in mid-October by the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security provides guidance for rapid testing in K-12 schools. To assess the approach described in the report, The Rockefeller Foundation signed a memorandum of understanding with HHS, which is sending at least 120 000 Abbott BinaxNOW tests to 5 pilot areas: Louisville, Kentucky; Los Angeles; New Orleans; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and Rhode Island.

Meeting Demands

As orders pile up for tests with an EUA, some observers question whether the US has the capacity to manufacture the hundreds of millions of tests that would be needed for frequent rapid testing.

For example, the $300 BD Veritor test processing device provided by the federal government to a Virginia nursing home came with enough tests to last only a few weeks, and the manufacturer expected it would be weeks before it could ship out more supplies, the New York Times reported September 29.

Quidel, which was manufacturing 2.1 million tests a week in early October, aims to ramp up production to nearly 6 million tests a week by mid-2021, Bryant said.

When the FDA granted the BinaxNOW test EUA, Abbott said it would ship millions of tests in September and 50 million tests per month beginning in October. Whether that goal has been met isn’t clear, although, apparently, the federal government is beginning to receive some of the 150 million tests it ordered the day after BinaxNOW received the EUA.

The Indian Health Service received 300 000 of the tests, which it said will be distributed to eligible health programs that care for students in Bureau of Indian Education–funded schools and at tribal institutions of higher learning, older adults in congregate living facilities, and other special needs populations. As far as who will get the millions of other tests purchased, HHS Secretary Alex Azar, JD, has said only that they will go to K-12 students and teachers, colleges and universities, first responders, “and other priorities as governors deem fit.”

Herrera thinks each state should manufacture rapid tests for its residents and then distribute them first to areas with a high prevalence of infection. Bringing the cost down to $1 a test would likely be possible only if the government subsidized it, he said.

“The government has invested billions of dollars into vaccine development,” Herrera noted. “We also need to invest similar amounts of dollars to improve diagnostics. A vaccine isn’t the golden ticket to a healthy world.”

For now, though, the federal government appears to have no nationwide SARS-CoV-2 testing plan other than purchasing the 150 million BinaxNOW tests, which has spurred 10 governors to form a bipartisan pact with The Rockefeller Foundation to obtain 500 000 rapid antigen tests apiece for their constituents.

“Beating back this pandemic requires a massive scale-up of rapid screening testing to 200 million a month,” Rajiv Shah, MD, Rockefeller Foundation president, said in a statement. “Right now…we aren’t even at 25 million a month.”